Abstract

War has been associated with direct trauma—physical injury, displacement, and loss. However, the reach of war extends beyond those who are physically present in conflict zones. Through news media, social networks, and cultural narratives, people around the world are exposed to the horrors of war, often experiencing emotional and psychological distress as a result. This phenomenon, known as vicarious or secondary trauma, is increasingly recognized as a significant public health and social issue. Media professionals who are indirectly exposed to news and pictures of war conflicts may experience war trauma. This is secondary or vicarious trauma. The findings of a survey conducted in Pakistan are analyzed critically to see the psychological indicators of trauma and how secondary experience influences the work functioning of the media personnel.

Introduction

War has been a persistent companion to humanity throughout history, leaving deep scars on societies, economies, and cultures worldwide. It is a state of armed conflict characterized by violence, loss, and displacement, often raising profound questions about its causes, consequences, and impact on human lives. War's effects on humanity are multifaceted and far-reaching. Some of the most significant consequences include loss of Human Lives ( Armed conflicts result in the deaths of soldiers and civilians alike, leaving behind grieving families and communities). Loss of life in war is not only tragic on a personal level but also has a profound impact on the social fabric of a society. Physical and Psychological Trauma (War inflicts severe physical injuries and psychological trauma on individuals, often leading to long-term mental health issues such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression, and anxiety), further, displacement and Refugee Crises (Wars force people to flee their homes, leading to massive displacement and refugee crises. Displaced individuals face uncertainty, hardship, and often, a loss of identity), finally, economic Instability and Poverty (economic consequences of war are staggering, with governments spending billions of dollars on weapons, soldiers, and logistics. This money could be used for education, healthcare, and infrastructure development, but instead, it is diverted to the military.

The economic ramifications are substantial, encompassing destroyed infrastructure, disrupted trade, and long-term developmental setbacks. Furthermore, war profoundly affects the psychological well-being of individuals, leading to a range of severe mental health issues, such as post-traumatic stress disorder, depression, and anxiety, which can persist long after the conflict ends (Khan & Altalbe, 2023). The extensive exposure to such traumatic events, even indirectly through media, can lead to chronic psychological distress among populations far removed from the direct conflict (Al-Ajlouny et al., 2025). This phenomenon, often termed vicarious or secondary trauma, highlights how continuous media exposure to war-related content can significantly impact mental health, even for those not directly involved in the conflict (Fekih‐Romdhane et al., 2023). For media professionals, this indirect exposure is an occupational hazard, often leading to significant psychological burdens and affecting their work functioning (Shilpa et al., 2023). Recognizing the ubiquity of armed conflicts globally (Williamson & Murphy, 2025), understanding the psychological consequences for various professional groups, especially those who mediate public understanding of these events, becomes paramount. This study aims to critically analyze survey findings from Pakistan to identify psychological indicators of trauma and assess how secondary exposure to war influences the work functioning of media professionals (Fekih‐Romdhane et al., 2023).

Dynamics of Secondary /vicarious Trauma

The history of wars has established that, long-term or short-term, the effects of wars end in unprecedented loss, and the experience of such traumatic events on all segments of the community is devastating. The experience of any trauma has direct or indirect effects. Literature has well established that indirect experiences may also cause trauma among the masses. This kind of trauma is called secondary trauma or vicarious trauma. War has historically been associated with direct trauma—physical injury, displacement, and loss. However, the reach of war extends beyond those who are physically present in conflict zones. Through news media, social networks, and cultural narratives, people around the world are exposed to the horrors of war, often experiencing emotional and psychological distress as a result. This phenomenon, known as vicarious or secondary trauma, is increasingly recognized as a significant public health and social issue. Vicarious experiences of war refer to the indirect exposure to war-related trauma through secondhand accounts, media, or relationships with affected individuals. Unlike direct trauma, which results from personal involvement in conflict, vicarious trauma is experienced by those who witness, hear about, or empathize with the suffering of others. Research shows that vicarious exposure to war can lead to symptoms similar to post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), anxiety, depression, and emotional numbing (Figley, 1995; Dekel & Baum, 2010). Children and adolescents are particularly vulnerable, as they may lack the cognitive and emotional resources to process distressing information. Communities exposed to war narratives may experience heightened fear, mistrust, and changes in social cohesion. These impacts can manifest as increased prejudice, solidarity, or shifts in collective memory and identity (Bar-Tal, 2007).

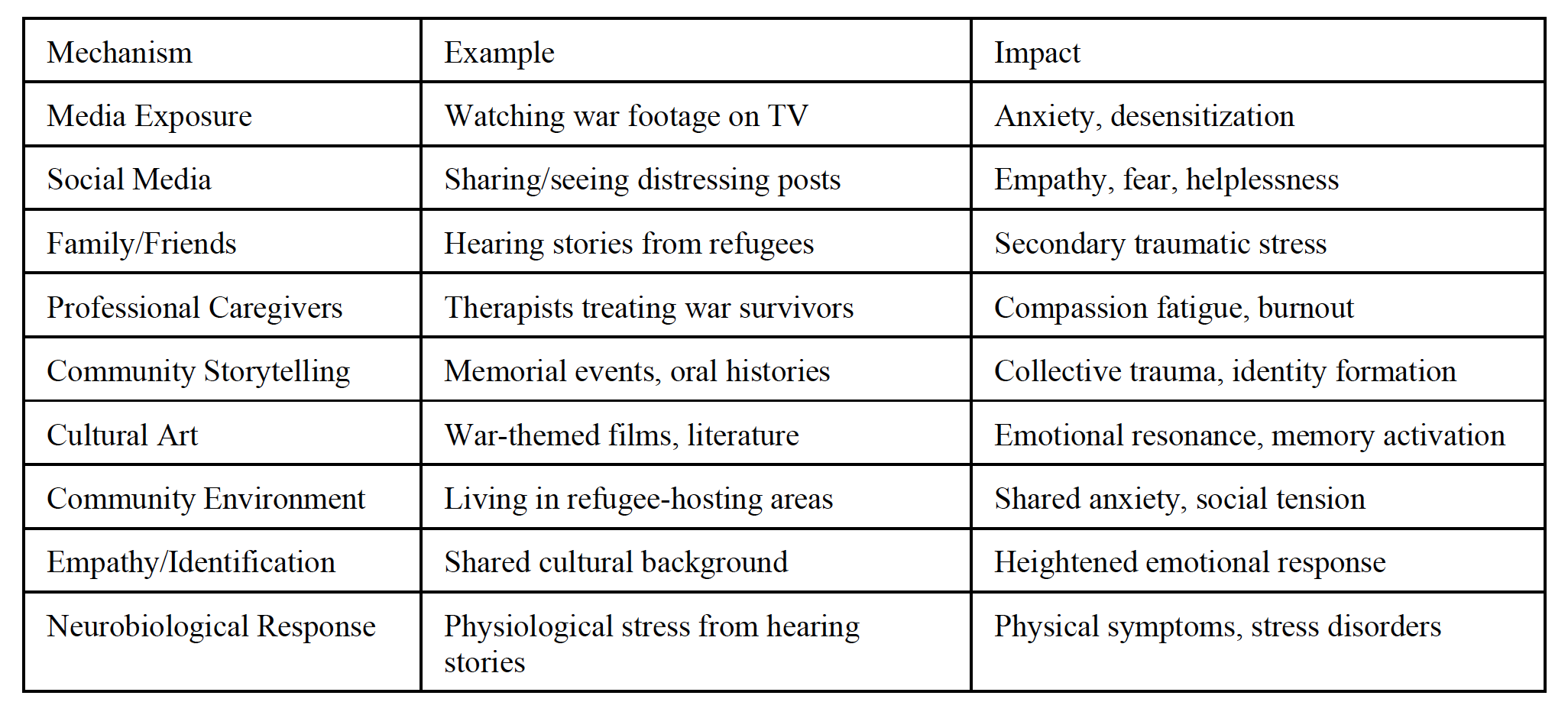

Secondary trauma is transmitted through:

- Media coverage (television, internet, social media)

- Interpersonal relationships (family, friends, community leaders)

- Cultural rituals and commemorations

Bandura’s Social Learning Theory posits that individuals learn behaviours and emotional responses by observing others. Media and community narratives about war can shape attitudes, beliefs, and emotional states, even in the absence of direct experience. Collective trauma refers to the psychological impact of traumatic events shared by a group or community. War, as a collective trauma, can alter community identity, values, and social norms (Alexander, 2004). Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Theory emphasizes the interconnectedness of individuals and their environments. Vicarious experiences of war can affect individuals at multiple levels—personal, familial, community, and societal. The following table best illustrates the mechanism through which secondary or vicarious trauma impacts the community and systems:

The process of transformation becomes more convenient for professionals who are exposed to traumatic content or material as part of their profession or responsibilities. Journalism or Mass communication is one of the professions which are exposed to traumatic material, and individuals working on their jobs can not avoid the traumatic experiences embedded in such material, where news of brutal attacks, pictures of dead bodies, bloodshed and violence everywhere is a common factor.

Empirical Findings

A survey conducted as part of a large-scale project in Pakistan (Suleman, Malik, Hanif, 2023) focused on media personnel who work on war- or trauma-related news in any capacity, whether as a field news reporter, a desk or office bearer, etc. A total of 300 media persons were selected for the survey. Major objectives of the survey were:

- To measure the psychological indicators as an impact of war trauma on media personnel

- To investigate the relationship of secondary trauma with the work-related functioning of media persons.

Secondary/Vicarious trauma was measured using the Vicarious Trauma Scale (Vrklevski & Franklin, 2008), an eight-item self-report measure rated on a 7-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree). The scale assesses cognitive, emotional, and psychological impacts of exposure to work-related traumatic material, with higher scores indicating greater vicarious traumatization.

Work functioning was assessed using the Work-Related Functioning Impairment Scale (Marx, Schnurr, Lunney, Bovin, & Keane, 2018), a 21-item self-report measure rated on a 7-point Likert scale. Seventeen items are reverse-scored. The scale evaluates impairment across multiple domains of occupational functioning in individuals exposed to work-related trauma, with strong internal consistency (α = .91 in the original validation study).

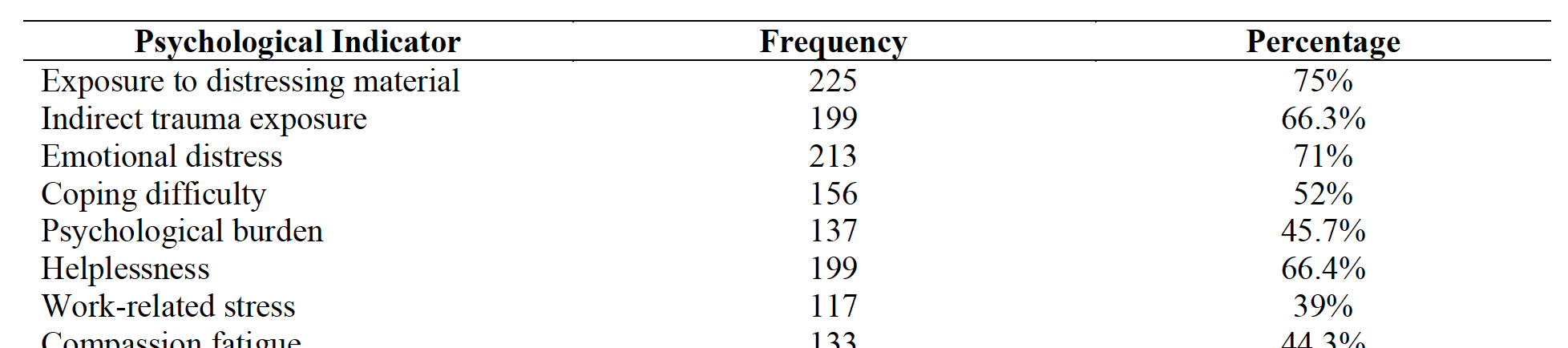

The findings in the table highlight the substantial psychological burden news reporters experience due to their occupational demands. The majority of respondents reported exposure to distressing material (75%), defined as the repeated contact with graphic or traumatic content through reporting, which was the most prevalent experience among crime reporters, consistent with the nature of crime journalism that routinely involves covering traumatic events such as violence, accidents, and victimization. This aligns with vicarious trauma theory, which posits that repeated exposure to traumatic content, even indirectly, can have significant emotional and cognitive consequences for professionals (McCann & Pearlman, 1990). Indeed, more than two-thirds of reporters also reported indirect trauma exposure (66.3%), hitch refers to experiencing trauma symptoms vicariously through victims’ narratives and stories, highlighting the strong presence of secondary traumatic stress in this group, suggesting that their contact with traumatized clients and victims frequently translates into secondary traumatic stress, a well-documented phenomenon among helping professionals and journalists (Buchanan & Keats, 2011, Simpson & Coté, 2006 ).

Closely tied to this exposure is the high rate of emotional distress (71%), understood as intense negative emotional reactions such as sadness, anxiety, or fear in response to their work. And helplessness (66.4%), which reflects the internalization of trauma narratives and the frustration of being unable to intervene directly in victims’ suffering. This mirrors findings from research on compassion fatigue, where emotional involvement with others’ pain often results in psychological exhaustion and loss of efficacy (Figley, 1995). Moreover, more than half of reporters acknowledged coping difficulties (52%), meaning challenges in using effective strategies to manage stress, while nearly half experienced psychological burden (45.7%), the subjective sense of mental heaviness and exhaustion caused by prolonged exposure to suffering. These indicators underscore the difficulty many reporters face in managing occupational stressors, echoing literature which suggests that maladaptive coping strategies exacerbate the impact of vicarious trauma (Keats & Buchanan, 2012).

Interestingly, compassion fatigue (44.3%), the emotional exhaustion resulting from sustained empathic engagement with others’ trauma, was reported by nearly half of the reporters, consistent with research on burnout and secondary traumatic stress in journalism and other caring professions. Work-related stress (39%), which refers to pressures from deadlines, workload, and organizational demands, was somewhat less prevalent but still significant, reported by a considerable proportion, though at somewhat lower levels than direct emotional distress and trauma exposure. Compassion fatigue, conceptualized as the convergence of burnout and secondary traumatic stress (Figley, 1995), appears as a significant risk for nearly half of the sample, reinforcing previous evidence that journalists in trauma-related beats are vulnerable to emotional exhaustion and detachment (Pyevich, Newman, & Daleiden, 2003). The comparatively lower proportion reporting general work-related stress suggests that while organizational pressures such as deadlines and workload remain relevant, the more salient challenges for crime reporters stem from the psychological toll of repeated exposure to human suffering rather than logistical or structural work stressors alone (Dworznik & Grubb, 2007).

Taken together, these results emphasize the need for interventions that strengthen resilience, enhance coping strategies, and provide organizational support systems for crime reporters. Structured peer support, trauma-awareness training, and workload management policies could help mitigate the risks of secondary traumatic stress and compassion fatigue. Consistent with theories of vicarious trauma and compassion fatigue, these findings demonstrate that journalistic exposure to violence and suffering is not merely a professional challenge but a profound occupational health concern that requires recognition and preventive action.

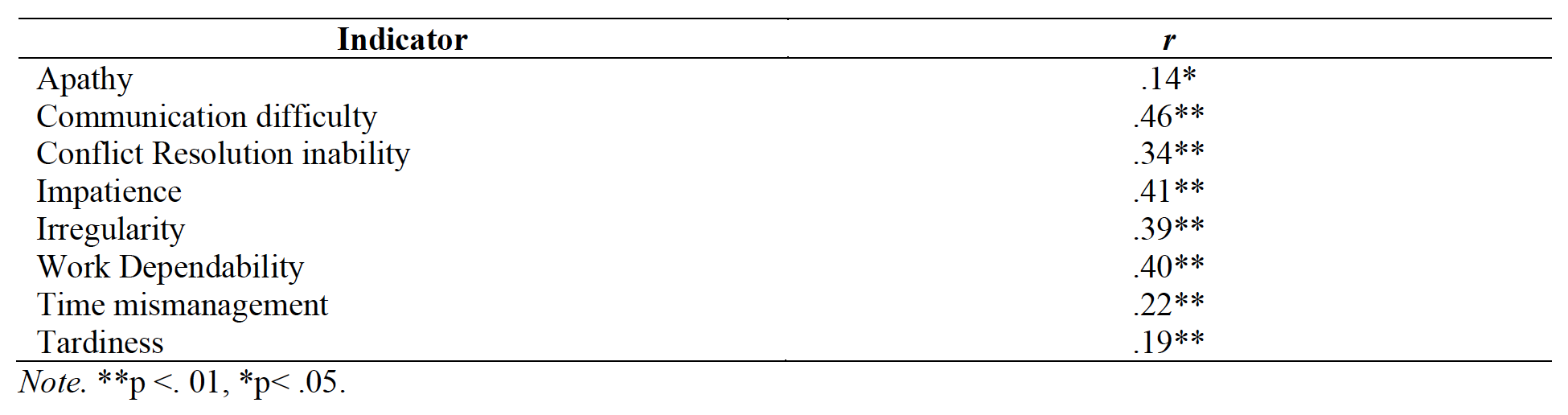

The correlation table highlights work-related functioning impairment’s psychological indicators that are significantly associated with vicarious traumatization. Apathy (r = .14, p < .05), defined as a lack of motivation or emotional responsiveness toward work, shows only a weak relationship. This suggests that while apathy can influence outcomes, it is not the strongest predictor in this context. Research has shown that apathy is often linked to disengagement and burnout, but it usually interacts with stronger predictors such as poor communication or time mismanagement (Le Heron et al., 2022).

The strongest association emerges with communication difficulty (r = .46, p < .01), which refers to challenges in expressing ideas and emotions effectively. This indicates that individuals struggling with communication are significantly more vulnerable to negative outcomes. The importance of communication is well documented; for example, poor communication in workplace and healthcare contexts has been linked to stress, errors, and interpersonal strain (Ting et al., 2023). Similarly, the inability to resolve conflicts constructively (r = .34, p < .01) shows a moderate correlation. Inability to resolve disputes increases stress levels and impairs group functioning, consistent with the literature linking conflict management skills to overall psychological well-being (Park & Kim, 2022).

Emotional regulation issues also stand out. Impatience (r = .41, p < .01), defined as a low tolerance for delays or frustration, shows a strong relationship with the outcome, highlighting how emotional reactivity contributes to stress and performance decline. Alongside this, irregularity (r = .39, p < .01) and inconsistency in behaviour or routine further predict difficulties, aligning with evidence that irregularity undermines self-regulation and productivity (Shah et al., 2021). Interestingly, work dependability (r = .40, p < .01), defined as reliability in fulfilling duties, also shows a positive correlation. Depending on the outcome variable, this may suggest that highly dependable individuals could be more susceptible to strain, perhaps because they overcommit or take on disproportionate responsibilities, a phenomenon supported in occupational stress literature (Peiró et al., 2020).

Indicators of behavioural discipline further emphasize the role of self-management. Time mismanagement (r = .22, p < .01), or poor planning and task prioritization, shows a weaker but still significant association, suggesting that inefficient scheduling undermines outcomes, though less strongly than interpersonal skills. Similarly, tardiness (r = .19, p < .01), defined as habitual lateness, correlates weakly but significantly, indicating its contribution as a minor yet relevant factor. Together, these indicators highlight that while apathy, time mismanagement, and tardiness have weaker effects, the strongest risks lie in difficulties with communication, conflict resolution, impatience, and work dependability. Overall, the findings align with theories of occupational stress and burnout, which emphasize the combined influence of interpersonal skills, emotional regulation, and time management on performance and psychological well-being. Strong associations with communication and emotional regulation support existing evidence that these are key mechanisms underlying workplace strain, while weaker but significant associations (apathy, tardiness) suggest they may act as secondary or compounding risk factors.

In conclusion, this article has shed light on the pervasive and often overlooked issue of secondary trauma among media professionals in Pakistan operating within war-affected regions. The findings underscore a significant impact on their work functioning, manifesting in various psychological and professional challenges. By highlighting the unique vulnerabilities of these individuals, this paper emphasizes the critical need for robust psychological support systems, organizational interventions, and policy reforms aimed at mitigating the adverse effects of prolonged exposure to traumatic events. Future research should explore longitudinal studies to track the long-term impacts of secondary trauma and evaluate the efficacy of different support mechanisms in improving the resilience and well-being of media professionals in similar high-risk environments. Ultimately, safeguarding the mental health of those who report on conflict is not merely an ethical imperative but also essential for maintaining the integrity and effectiveness of informed public discourse.

References

Le Heron, C., Apps, M. A., & Husain, M. (2022). The neuroscience of apathy: Pathophysiology and treatment. Translational Psychiatry, 12(1), 1–12. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41398-022-02292-3.

Ting, S. C., Chen, H. H., & Hsieh, Y. C. (2023). Communication quality and workplace stress: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 28(2), 153–169. https://doi.org/10.1037/ocp0000331.

Park, S. Y., & Kim, J. H. (2022). Conflict management strategies and employee well-being: A systematic review. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 947220. https://doi.org/10.1037/ocp0000331.

Shah, A., Kumari, S., & Singh, R. (2021). Irregular work routines and psychological outcomes: The mediating role of self-regulation. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(17), 9254. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18179254.

Peiró, J. M., Bayona, J. A., Caballer, A., & Di Fabio, A. (2020). The importance of work characteristics affects the well-being of workers: A person-centred approach. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 1917. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01917.

McCann, I. L., & Pearlman, L. A. (1990). Vicarious traumatization: A framework for understanding the psychological effects of working with victims. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 3(1), 131–149. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00975140.

Buchanan, M., & Keats, P. (2011). Coping with traumatic stress in journalism: A critical ethnographic study. International Journal of Occupational and Environmental Health, 17(4), 313–322. https://doi.org/10.22230/cjc.2012v37n1a2537.

Keats, P., & Buchanan, M. (2012). Covering trauma in Canadian journalism: A survey of attitudes, policies, and support. Canadian Journal of Communication, 37(1), 15–37.

Pyevich, C. M., Newman, E., & Daleiden, E. (2003). The relationship among cognitive schemas, job-related traumatic exposure, and posttraumatic stress disorder in journalists. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 16(4), 325–328. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1024422220161.

Dworznik, G., & Grubb, M. (2007). Preparing for the worst: Making a case for trauma training in the journalism classroom. Journalism & Mass Communication Educator, 62(2), 190–210. https://doi.org/10.1177/107769580706200205.

About the Authors

Dr. Noreeta Sulaiman. Noreeta Suleman is working as a Research Associate cum Lecturer at the National Institute of Psychology. noreeta@nip.edu.pk

Dr. Rubina Hanif. Contact: drrubinahanif@nip.edu.pk