Violence, including intimate partner violence (IPV) and domestic violence (DV), remains a serious global issue with pervasive consequences for the victims’ health, safety, and well-being. IPV and DV are not unique to any one culture or faith; their perpetuation is shaped by inappropriate conditioning, development of diseased role models, unhealthy social reinforcements/ cultural norms, and religious (mis)interpretations. This article examines IPV and DV within Canadian-Muslim communities, exploring how migration, acculturative stress, collectivist values, and patriarchal traditions intersect with religious (mis)interpretations to sustain cycles of violence through diseased role models and inappropriate social reinforcement. To dismantle these cycles of violence, this article suggests: (1) drawing on classical and operant conditioning, as well as psychodynamic frameworks, to better understand the roots of IPV and DV; and (2) exploring how healthy role models and positive social reinforcement patterns can be developed and transmitted across generations.

Domestic violence (DV) refers to abusive behaviour in any personal relationship where one partner seeks to gain power and control over the other (World Health Organization [WHO], 2025). Family violence encompasses abuse by spouses, parents, children, siblings, or extended relatives, whereas intimate partner violence (IPV) refers more specifically to abuse between current or former spouses, common-law partners, or dating partners (WHO, 2025; U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2024). Importantly, IPV occurs not only in heterosexual relationships but also in same-gender and gender-diverse relationships, which can involve a range of domestic and partner dynamics, including intimate partners, in-laws, and other familial or cohabiting individuals (Drouillard & Foster, 2024; Machado et al., 2024; Workman et al., 2022).

Here are some statistics referring to such issues, though not limited to, the Muslim communities. According to the World Health Organization (2025), violence against women and girls is universal, prevailing across countries, cultures, and religions, and rooted in social norms that privilege men over women. The World Health Organization (2024) estimates that 30% of women globally experience some form of abuse during their lifetimes. Canadian data reveal similar trends. Statistics Canada reports that nearly 6.2 million women have experienced domestic violence, and 60% of female homicides are linked to family violence, which is alarming (Government of Canada, 2025; Statistics Canada, 2005).

IPV and DV are not limited to women; men and all genders can also be victims. However, for the purpose of this article and to ensure clarity for readers, the term “victim” will be used to refer specifically to women. This focus is supported by various studies that consistently show women comprise the majority of victims in such cases. For example, Beeby (2012), in their Globe and Mail article, quotes the Annual Statistics Canada telephone survey in 2009, which found that approximately 336,000 Canadians were victims of some form of violence perpetrated by their spouse and shared that more than 80% of those cases were women who were the victims. The report also highlights that the financial cost of domestic violence for that year was around $7.4 billion.

As previously mentioned, IPV and DV occur across all religious groups; however, this article closely examines Muslims, who represent the second-largest religious group in Canada, numbering approximately 1.8 million people (4.3% of the population) (Statistics Canada, 2022; Statistics Canada, 2025). The majority (68%) are foreign-born and navigate processes of migration, resettlement, and acculturation (Environics Institute for Survey Research, 2016). For many immigrant Muslim families, collectivist traditions intersect with Canadian individualist norms, complicating how IPV is understood, reported, and addressed.

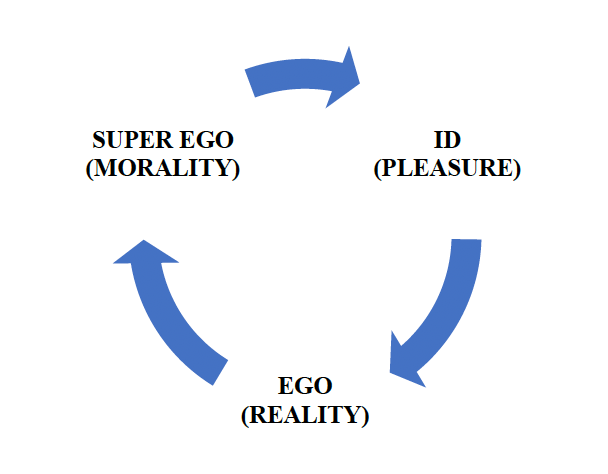

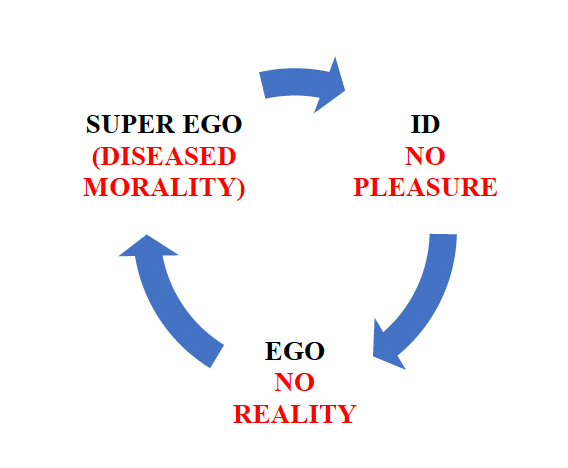

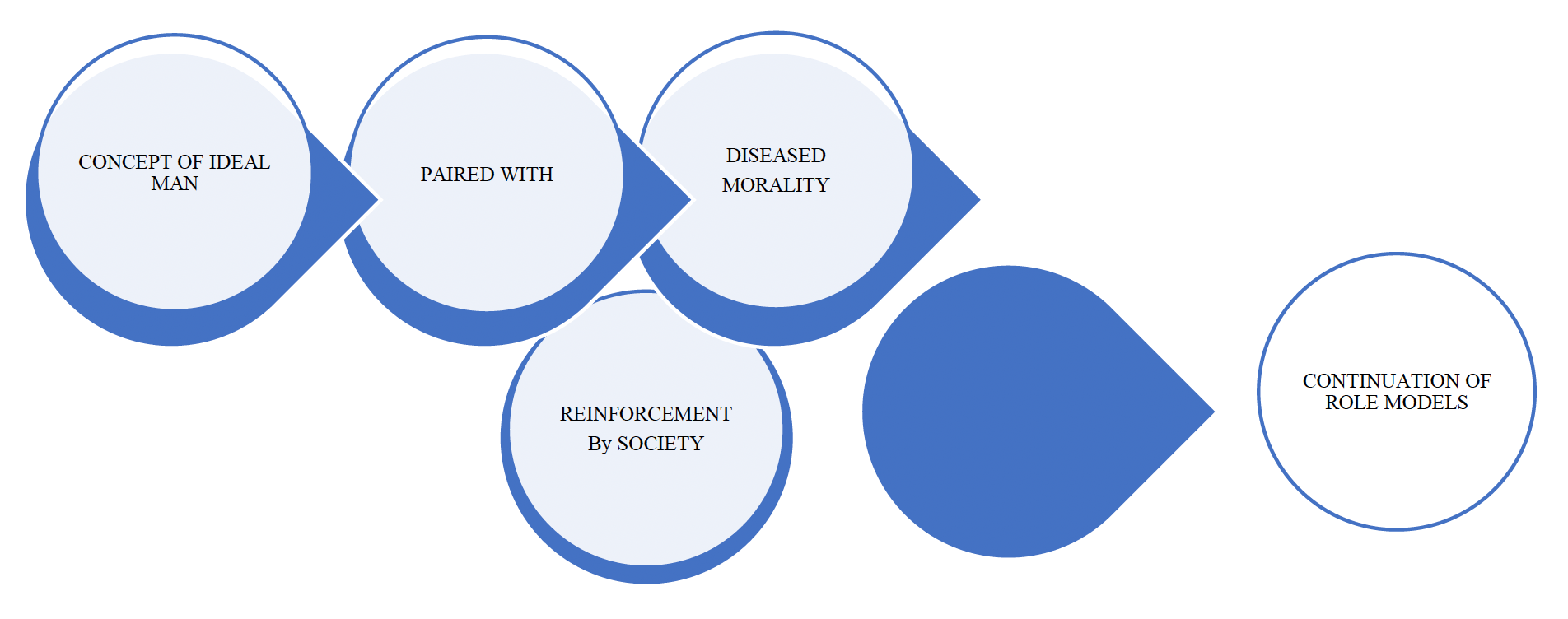

While working closely with 48 clients from Muslim backgrounds in a clinical setting, Dr. Akram-Pall (2025) conducted a survey and found that patterns of IPV and DV could be explained by classical and operant conditioning. These learning mechanisms help account for the development of diseased role models and inappropriate social reinforcement patterns, which contribute to the persistence of IPV and DV across generations. In a conference presentation (Akram-Pall, 2025), she explained that these patterns can be replaced with healthy role models and positive social reinforcement by applying classical and operant conditioning frameworks. This approach, she suggested, can ultimately reduce—and potentially eliminate—the development, persistence, and intergenerational transmission of such behaviours. During her presentation, she emphasized the importance of healthy parenting and societal norms in preventing and eliminating IPV and DV in our society. Classical conditioning explains how survivors of IPV and DV may develop conditioned fear responses to cues associated with abuse. Over time, neutral stimuli (tone of voice, gestures, household sounds) become paired with threat, eliciting anxiety or compliance (Grant, 1964). As for perpetrators, aggression becomes conditioned to elicit outcomes such as submission or silence, reinforcing its use. Eventually, due to societal, cultural, and patriarchal norms, dominating and controlling behaviour becomes associated with notions of “masculinity” and a “diseased role model,” a connection further reinforced through operant conditioning and social reinforcement. Operant conditioning highlights reinforcement cycles: perpetrators receive positive reinforcement (such as power, control, or status) or negative reinforcement (the cessation of arguments), which strengthens violent behaviours. Survivors may learn submissiveness through negative reinforcement (avoiding harm by compliance), thereby perpetuating the cycle (Grant, 1964). These contingencies create deeply ingrained behavioural patterns that sustain IPV across generations unless disrupted. This interplay of classical and operant conditioning is illustrated in Figures 1 and 2.

Drawing on Freud’s tripartite model (Id, Ego and Superego), many women in abusive contexts present with a repressed id (denied pleasure), an underdeveloped ego (limited capacity for reality-testing), and an exaggerated superego dominated by fear (see Figure 1) (Boag, 2014; Freud, 1923/1961). Whereas many men in an abusive context exhibit the id (pleasure principle), a confused ego (blurred vision based on societal configuration of reinforcement from society and continuation of role models), and an overpowered superego (Figure 2). This diseased morality produces internalized guilt and anxiety, often manifesting in depression, obsessive-compulsive tendencies, and other mental health challenges, which lead to the continuation of abuse and violence in a society. There are several examples of IPV and DV of honour killing where diseased morality played a critical role rather than logical thinking and cognition (Gabbay, 2023).

Collective Cultural Values and Norms, Religious (mis) Interpretations, and Role Models in Muslim Social Contexts

In this section, a few related factors are discussed to explain the role of collective cultural values and norms, religion (mis) interpretations, and Role Models in Muslim social contexts based on personal observations and life experiences.

Development of Moral Values Based on Fear and Religious Misinterpretations

Fear-based morality arises when religious texts are (mis)interpreted to enforce submission, silence, and obedience among women. Rather than cultivating moral consciousness and healthy personality development, these frameworks lead to segregation, oppression, and violence.

Role Models and Social Learning Context

When children are raised in social contexts where IPV is accepted and normalized, these learned social patterns are passed on to the next generation from an early age, and they continue to strengthen over time through positive reinforcement and appreciation. This social learning process cultivates and supports IPV in close-knit cultures. For example, boys are appreciated when they may exhibit dominance and control, and girls are respected when they are submissive and vulnerable. Eventually, these role models and social learning contexts contribute to increased IPV over time.

Psychogenic Mutism

Psychogenic mutism also refers to selective mutism/silence, where individuals interactively participate and communicate in specific issues, but for others, they are mute and non-participating. In collective cultures, women are expected to remain silent to preserve family values and cultural traditions, as they are considered responsible for holding the family together. If any woman attempts to raise her voice against violence, which is not approved by the collective culture, she can be socially abandoned, which makes her feel segregated and alienated. At times, due to social abandonment, she ends up returning to the cultural norms and prefers to tolerate violence and transfer the message of silence to the next generations.

Migration and Cultural Integration Stress

Migration adds complexity to IPV experiences. Homeland traditions and cultural expectations are brought to the Canadian context with migration. Women are often forced to follow the same traditions and norms that were practiced in their original homelands, including dress codes and family rules. However, for men, these rules are often more lenient and flexible, depending on the weather and situation. If these traditional norms are not followed, women may be labelled as liberated and excluded from the cultural network, leading to segregation.

This article attempts to deconstruct diseased moralities rooted in fear and misinterpretations of religion in the Muslim community and elaborates on the importance of healthy parenting and the development of societal reinforcement patterns that can support equity, mental health, and social harmony. The roles of parenting and societal pressure are highlighted, as they play a critical role in developing, nurturing, and strengthening the diseased morality. This is achieved through classical conditioning and operant conditioning frameworks, which aim to unlearn these patterns by learning ways to generate healthy role models. This will eventually lead to the elimination of abuse and violence by cultivating respect and dignity. It is recommended to conduct future studies to analyze these patterns, which persist in continuation of IPV and DV, and to educate society, particularly Muslims, about these patterns to eliminate the curse of IPV and DV, which is a heavy cost on the entire society, both psychologically and financially.

Empirical Insights

Research on Canadian Muslim women experiencing IPV by Alghamdi, Lee, and Nagy (2021) highlights themes of:

- Childhood exposure to trauma and violence.

- The “iron cage” of societal expectations.

- Fusion of love and violence in intimate partnerships.

- Post-migration challenges, including limited social support.

- Severe psychological and physical consequences of IPV.

Straus’ General Systems Theory (1973) situates IPV as a product of cultural, societal, and familial values. For many Muslim immigrant women, adverse childhood experiences, poverty, and illiteracy shape adult vulnerabilities, while collectivist norms complicate disclosure and intervention.

Toward Healthier Role Models

The perpetuation of IPV through conditioning can be visualized as two parallel pathways:

Distorted Model

- Classical Conditioning: Pairing male dominance with authority and female submission with virtue.

- Operant Conditioning: Reinforcing men’s aggression with social approval (e.g., honour killings, control).

Healthy Model

- Classical Conditioning: Pairing respect, compassion, and equity with family and marital success.

- Operant Conditioning: Reinforcing nonviolence and gender equity through community recognition, legal protection, and religious education.

Morality Framework

- Early childhood experiences lead to personality development

- Healthy parenting leads to healthy morality

To dismantle IPV, societies must reinforce healthy models and disrupt distorted ones through:

- Religious reinterpretation is rooted in compassion and equality.

- Policy and laws that penalize violence and reward equity.

- Community activism that normalizes women’s participation in decision-making.

- Clinical interventions that address fear, trauma, and conditioning cycles.

- Future studies to explore these conditioning cycles and morality frameworks.

Conclusion

Violence (IPV and DV) among Muslim communities in Canada reflects a convergence of behavioural conditioning, patriarchal norms, migration stress, and religious misinterpretations. Violence (IPV and DV) is sustained not only by individual pathology but also by role models and reinforcements that valorize domination and submission. By reorienting conditioning processes toward healthy role models, grounded in both religious teachings and modern equity frameworks, we can promote lasting change. Violence is not inherent to Islam or Muslim communities, but results from diseased moralities that must be challenged through collective, cultural, and psychological transformation.

References

Akram-Pall, S. (2025, July 20). Conference presentation. Paper presented at the 2025 AMIC Annual Conference, Mississauga, ON, Canada. Al-Mawrid Institute Canada & Sinai Foundation Canada.

Alghamdi, M. S., Lee, B. K., & Nagy, G. A. (2021). Intimate partner violence among Canadian Muslim women. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 37(17–18), NP15153–NP15175. https://doi.org/10.1177/08862605211021516

Beeby, D. (2012, December 23). Spousal violence costs billions of dollars per year, a major study finds. The Globe and Mail. https://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/national/spousal-violence-costs-billions-of-dollars-per-year-major-study-says/article6698908/

Boag, S. (2014). Ego, drives, and the dynamics of internal objects. Psychoanalytic Quarterly, 83(2), 309–338. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2167-4086.2014.tb00559.x

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024, May 16). About intimate partner violence. National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. Retrieved August 29, 2025, from https://www.cdc.gov/intimate-partner-violence/about/index.html

Drouillard, K. J., & Foster, A. M. (2024). “It definitely changed me”: Exploring sexual and gender diverse people’s experiences with intimate partner violence in Ontario, Canada. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, 56(4), 368–377. https://doi.org/10.1111/psrh.12276

Environics Institute for Survey Research. (2016, April). Survey of Muslims in Canada 2016 [Final report]. Retrieved August 30, 2025, from https://www.environicsinstitute.org/docs/default-source/project-documents/survey-of-muslims-in-canada-2016/final-report.pdf

Freud, S. (1961). The ego and the id (J. Strachey, Ed. & Trans.). W. W. Norton & Company. (Original work published 1923)

Gabbay, S. M. (2023). Forgotten victims: Male honour killings in Muslim societies. Asian Social Science and Management, 27(3), 561–578. https://doi.org/10.63002/assm.27.561

Government of Canada. (2025, August 5). Intimate partner violence [Fact sheet]. Women and Gender Equality Canada. Retrieved August 29, 2025, from https://www.canada.ca/en/women-gender-equality/gender-based-violence/intimate-partner-violence.html

Grant, D. A. (1964). Classical and operant conditioning. In Classical conditioning (pp. 39–54). Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-1-4832-3145-7.50006-6

Kimmes, J. G., Mallory, A. B., Spencer, C., Beck, A. R., Cafferky, B., & Stith, S. M. (2019). A meta‐analysis of risk markers for intimate partner violence in same‐sex relationships. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 20(3), 374–384. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838017708784

Machado, P. H. M., Sousa, A., & Cunha, P. (2024). Bidirectional violence in intimate relationships: A systematic review. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1177/15248380231193440

Straus, M. A. (1973). A general systems theory approach to a theory of violence between family members. Social Science Information, 12(3), 105–125. https://doi.org/10.1177/053901847301200307

Statistics Canada. (2005, July 14). Family violence in Canada: A statistical profile (Catalogue No. 85-224-X2005000 ENG) [PDF]. Canadian Centre for Justice Statistics. Retrieved August 29, 2025, from https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/85-224-x/85-224-x2005000-eng.pdf

Statistics Canada. (2022, October 26). The Canadian census: A rich portrait of the country’s religious and ethnocultural diversity [The Daily]. Retrieved August 26, 2025, from https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/221026/dq221026b-eng.htm

Statistics Canada. (2025, June 18). Canada’s population estimates, first quarter 2025 [The Daily]. Retrieved August 28, 2025, from https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/250618/dq250618a-eng.htm

Tohin, S. S. (2015). Combating spousal violence in the Muslim community of Canada: An overview in the context of the province of Ontario. IOSR Journal of Humanities and Social Science, 20(11), 26–37. https://doi.org/10.9790/0837-201152637

United Nations Entity for Gender Equality and the Empowerment of Women (UN Women). (2014). Violence against women [In Focus]. UN Women. https://www.unwomen.org/en/news/in-focus/end-violence-against-women/2014/violence

Workman, A., Kruger, E., Micheal, S., & Dune, T. (2022). LGBTIQ CALD people’s experiences of intimate partner violence: A systematic literature review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(23), 15843. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192315843

World Health Organization. (2008, November 25). International Day for the Elimination of Violence against Women [Speech]. Retrieved August 28, 2025, from https://www.who.int/director-general/speeches/detail/international-day-for-the-elimination-of-violence-against-women

World Health Organization. (2024, March 25). Violence against women [Fact sheet]. Retrieved August 30, 2025, from https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/violence-against-women

About the Authors

Shawal Pall, Ph.D. Fairleigh Dickinson University, United States of America. Contact: pallshawal@gmail.com

Saadia Akram-Pall, Ed.D. University Of Toronto, Canada. Contact: drsaadiapall@gmail.com